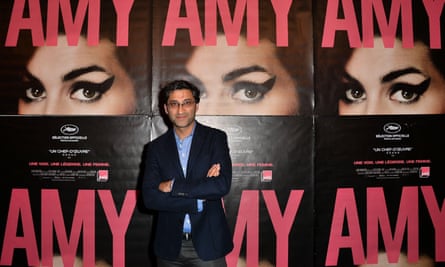

It was some time in the early 2000s and Asif Kapadia, already a successful film director, a wunderkind whose first feature in 2001, The Warrior, won the Bafta for outstanding British film, was travelling back from New York.

“There’s a beautiful, gorgeous sunset over Manhattan. I’m in a limo being taken to the airport. And I was taking photos of Manhattan because I was driving over Brooklyn Bridge and it’s just all so cinematic and I became subconsciously aware of the driver watching me in the rear view mirror.

“I get to the airport and I’m in the Virgin lounge when my name is called out. And I thought: ‘Have I left a bag or something?’ But then five or six people come: homeland security. And they stop me in the lounge in front of everyone, the only person of colour in there, and empty out my bag, and they say: ‘Someone’s reported you.’

“‘You’ve been acting suspicious.’ And it’s like: ‘Who are you? Why are you here? What were you doing?’”

An itinerary of his trip and its purpose proved his credentials and he was eventually allowed to go and boarded his flight. But for nearly a decade afterwards, he found himself on a “watch list”. “I would get stopped and interviewed two times before I got on a plane, pulled out in a room. I started realising that every time I show my boarding pass, instead of a green light going off, a red light goes off, and then you have to be taken somewhere for an interview.”

He avoided the US and when he could not avoid it, for example when he was working on his documentary Amy, about the singer Amy Winehouse, which wowed audiences and critics alike and which went on to win an Oscar, “I had to get a letter from my teacher”.

“Everyone else in the crew would go through and I’d get pulled up. I had to get a letter from the head of Universal to say: ‘Asif is working on this project for us.’”

Kapadia is three years into making his new film, 2073, when he tells me this story for the first time; how “being watched and paranoid” became his normal. He’s feeling it again. It’s a month or so after the atrocities of 7 October and the invasion of Gaza and every day feels like a new chapter in a global horror show. For Kapadia, an outspoken child of Muslim Indian immigrants working in a notoriously elitist and cowardly industry, it feels like there are extra dangers to navigate for anyone who speaks out.

He has invited me to his office in Somerset House because he wants to show me something. I’d met him a few years earlier and knew that he’d been working on a new project, set in 2073, and had got a message. He’d edited together some sequences. “And I thought I’d better show you,” he says as I sit down on a sofa and he turns on the screen. “Because you’re in it.”

It’s a plot twist I hadn’t seen coming, as I’d not sat down for an interview or done any filming, but the whole film is a plot twist: an urgently prescient and genre-defying sci-fi film set in “New San Francisco” in 2073. It’s a hugely creative blend of drama and documentary that unpicks the reasons behind a civilisational catastrophe. It’s called “The Event” in the film and we never find out what it was – nuclear war? climate collapse? – but Kapadia follows a thread that weaves together populist politicians, demagogues and tech billionaires to show how close to this disaster we already are.

It opens in cinemas in the US on 27 December and the UK from 1 January and although I am in it – more of that later – when I finally watch it, it’s the story of what happened to Kapadia after 9/11 that keeps coming back to me. His experience of being data-harvested, profiled and treated as “suspicious”, which is fed so directly into the film.

Ghost, the central character, played by Samantha Morton, lives underground in a deserted shopping centre. She is attempting to remain off the grid, out of sight, unprofiled. She has stopped speaking and we hear only an interior monologue. It’s 37 years after “The Event”, the unspecified cataclysm that upturned the world as we know it. And outside, the streets are dangerous: there are facial recognition cameras on every corner, drones flying overhead, armed police. It’s a world destroyed by terrifying fires, flood, war. Chairwoman Ivanka Trump is now in her 30th year of power.

The twist is that this isn’t the future. Much of the footage is archive taken from the present day: women and children on the Hong Kong subway being beaten by armed officers, drone shots of street after destroyed street in Gaza, biblical floods sweeping away blocks of flats. And in between these dramatic scenes with Morton, isolated and alone, able to trust no one, are documentary sequences that Kapadia calls “time capsules”.

“I hope someone finds this,” Ghost says. “No one did anything to stop them. It’s too late for me. I was alone. It may not be too late for you.”

It’s the “time capsules” that transport us squarely back into the present. Kapadia conducted interviews with dozens of journalists, activists and technologists that he interlaces with clips that take us from the populist politics of Nigel Farage, Donald Trump and Narendra Modi to the Silicon Valley bro-sphere – Elon Musk, Peter Thiel, Mark Zuckerberg. “How did we get here? How did we let that happen?” asks Ghost as we see her walking through New San Francisco’s streets, the sky a deathly orange, real footage from the fires of two years ago.

It’s a dazzlingly creative work. Kapadia started out directing fictional features but he is best known for his hugely popular and critically acclaimed sort-of trilogy of documentaries: Senna, Amy, DiegoMaradona. He pioneered a new aesthetic: gorgeously cinematic and defiant of the usual rules. And until 2073, in which he broke his own rule, his documentaries involved no talking heads, just archive overlaid with the voices of those who knew his subjects best, racing driver Ayrton Senna, singer Amy Winehouse and footballer Diego Maradona.

The works defy genre, he points out. And the more I speak to him, the more it seems this may be Kapadia’s core value: he himself defies genre. He charts his own course. Growing up in Hackney before the oat milk lattes arrived, his parents immigrants from India, he found himself in a notoriously tough comprehensive school in a tough neighbourhood where “you had to either be tough or loud to survive, and I wasn’t tough”.

He broke the rules from the off with his debut feature The Warrior, which he describes as a western, filmed in India, with a non-English speaking cast. Kapadia’s recent work has been commercially successful as well as being critically acclaimed, but early screenings of 2073 left his financiers puzzled.

The film directly challenges the Silicon Valley technology companies, and here is the central problem for anyone trying to make films or TV shows about such issues: US streaming platforms are themselves tech companies. “Well, you’re never going to sell that to Amazon,” said one of his backers after watching a sequence with its founder, Jeff Bezos, launching a rocket into space.

In fact 2073 will be available on Amazon and other platforms. But including Bezos, as well as the likes of Indian PM Modi and former Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro in his techno-authoritarian fable was a brave and principled decision, given the streamers’ commercial interests in the booming markets of India and Brazil. But it also reinforces the whole point of the film.

“I honestly thought, I don’t know what this is, I don’t know what’s going on in the world, I don’t fully understand it, but part of me kept thinking, this could be the last film that I made. And when I started making it, a lot of the things that are happening right now in the world, hadn’t actually started then, right? But I just got this feeling, this is quite serious and heavy.

“Generative AI didn’t exist when we started this film. Trump had just lost the election. Every American was saying: ‘Why do you have shots of him in the film? He’s finished, he’s old news. Everyone’s sick of him.’ And then by the time the film’s come out, he’s just won the election.”

I watch 2073 for the first time in the summer with an invited audience of journalists and activists who in some way helped and even though they all know some bits of the story, they’re still shocked by having it threaded together in a way that seems new and revealing and alarming: populist politics plus surveillance technology plus climate emergency equals our dystopian future – which is actually our dystopian present.

Kapadia explains how even the interrogation that Ghost receives after being profiled and targeted as “suspicious” is based on questions posed to Uyghur detainees in de-extremification and re-education camps in China.

I first met Kapadia in 2019 and he started talking about the project, but he had no idea what he was doing. “What is it?” I asked. I don’t know, he replied. “It’s sort of about everything that’s happening now.”

He began by just pulling on threads. “My family is from India, from Gujarat where Modi is from, so I was aware of what was happening there. How Muslims are being dehumanised, treated as animals. People are getting lynched. Then I was in America before the 2016 election. And I’ve worked in Brazil. I’ve worked in Argentina. My composer is Brazilian and his father was locked up in the dictatorship and the younger people on the Maradona crew were really nice people who kept saying: ‘It’s got so dangerous and so violent, we need a dictator, a strong man.’”

And where he landed was to try to show that his future imaginary American dystopia has already happened: in other countries such as India and the Philippines, where within just six months of being voted into power, Rodrigo Duterte crushed a democracy and launched a “war on drugs”. That war involved executing people in the streets while paid-for bots and trolls took it online against his enemies, the press.

after newsletter promotion

He was drawn to the story of Rana Ayyub, a Muslim investigative journalist in India, who has been harassed and targeted through lawsuits and prosecutions and relentless, overwhelming online abuse – and yet still carries on reporting. And Maria Ressa, the brilliantly articulate Filipino journalist, former CNN bureau chief and now Nobel peace prize laureate, who found herself arrested and facing prison after Duterte came to power. And, there was a third story that he wanted to cover, that of Brexit and the disruptive power of technology. It had been part of the unease that had fuelled his desire to make the film.

What I discover is that I’m the third of three female journalists he features. And it’s weird in a way I can’t quite explain because Kapadia, the expert collagist whose artistry restored Amy Winehouse from the raddled drug addict of the tabloid press to the talented tragic victim of a misogynist corrosive culture, has assembled, magpie-like, fragments of my work and woven them into his.

At the start of the project, during lockdown, he’d asked for a chat, a Zoom call, he’d recorded for research purposes. It’s 2020 and we’re living in another kind of sci-fi dystopia. Generally, for an official meeting, I position myself at a desk with a classic bookshelves/plants backdrop and will make an effort to at least brush my hair. But if I’m chatting informally, I quite often lounge at my kitchen table, as it turns out I did with Kapadia, not expecting four years later for that to turn up as a scene in a documentary.

“It was my editor who did it. He realised these overlaps in your experience with Maria and Rana. I had no idea that you knew each other. The interviews were done years apart.” He’d treated the research Zoom as found footage and cut it into the film with clips of my 2019 Ted Talk, entitled Facebook’s Role in Brexit and the Threat to Democracy. There’s a lesson in here about treating every Zoom call as though someone is recording it but I mostly felt – feel – a sense of relief. It’s the first time that a film-maker of Kapadia’s talents has turned his attention to a story that I’ve been desperate to see told.

An acute sense of urgency sustained him as he has navigated the long haul of getting it made. It is so unlike his other work, overtly political, engaged with the now, an epic, global big-picture view of what is happening in the world. And it’s landed at a moment when it couldn’t be more needed.

I watch it for the first time before Trump’s victory and for a second, afterwards, and it’s uncanny how prescient it is: tech bro in chief, Elon Musk, and the man behind the throne, Peter Thiel, both feature prominently. Thiel’s company Palantir, a defence contractor specialising in data profiling that works for the US state and now the NHS, is name-checked in 2073, its signs looming over the streets in New San Francisco while the voice of privacy campaigner Silkie Carlo talks of the “totalitarian architecture” of our digital world. “You only need a change of government,” she says. “And then it’s too late.”

Last week, I caught up with Kapadia by phone while he was waiting for a plane at JFK, the same place where he was picked out and placed on a watch list for a decade. If there’s one lesson from the film, it’s that the harvesting of our data puts us all on a potential watchlist. Kapadia has been at screenings in New York and LA and the film has become real for an audience there in a way it would not have done even a few weeks earlier.

“They really get the power of the tech bros now. Peter Thiel, Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos… they see this now. It’s happening right in front of their eyes,” he says. In Spain, recently hit by devastating floods in Valencia, it’s the climate sequence that the audience picked up on. The film, he says, is a “mirror” for the spectator. “I always watch it with the audience and everywhere I go, people respond differently.”

The comment stays with me because the lesson for me, and the power of it, is the emotion. Even though Ghost is a woman who has elected to stop speaking. “I kept on thinking, how do you make this feel like an emotional journey?” says Asif. “A story in order to affect change. Amy and Senna are both very, very emotional films.”

And so is 2073, even with the spareness of Morton’s character and the minimalist dialogue; her face and voiceover are pure emotion. Kapadia says that when Morton read the script she identified with the character immediately. “She said: ‘I grew up in children’s homes, that was my life. I had just a few belongings. I was always on the move.’”

There are so many layers. Kapadia includes clips from Morton’s own past in the film, memories that surface during sleep, including ones from her role as a psychic or “pre-cog” in the 2002 film Minority Report, in which she could predict the future. Ghost, explaining what happened to her grandmother – a woman from our own time – says that she defied the attempted to wipe out memory.

Ghost is an outsider. Kapadia’ admits that such figures recur in his work. It was a tutor at art school who first noticed that about his writing. “She said, they’re always about outsiders taking on power in some way, or some sort of system. And that’s before I’d made any long films, but they basically all have that thing. They’re always about people standing up to power. And sadly, it doesn’t always turn out that well for people.”

The outsiders are characters but maybe more than in his other films, it strikes me that Kapadia is the central character in this one. The industry outsider trying to warn the world, regardless of the personal cost. He could be directing Hollywood movies, or Netflix biopics. But, with every technology, the first victims are always people of colour, Muslims, women. And he too is a “pre-cog” ahead of the curve in understanding the trajectory we’re on. And the lesson he learned on the streets of Hackney is that survival depends on speaking up and out.

I notice also how he describes leaving school and falling into a job working on student films aged 17 as “running away”, like Ghost. During his GCSEs his mother, a machinist, who had schizophrenia, worsened and was sectioned. The experience made him decide to refuse to do A-levels. He didn’t want to be judged forever on a single day’s performance but on work created over a long period and vowed that he’d never take another exam.

Not only did he penetrate the rarefied world of film-making, getting to film school and art school, but he was a success from the off. He tells me how it’s “conscious” that the central characters in the film are women. “Everyone notices that. How it’s women who are taking on the fight.”

It doesn’t feel like a coincidence that growing up, the youngest of five, it was three feisty, political older sisters who got him reading first the Mirror, later the Guardian, and introduced him to Malcolm X, a copy of whose biography is a leitmotif in the film. “There was also a very kind of, like, strong female kind of presence in my life. And they very much were the ones that were very political, growing up in Hackney, they were all quite strong feminists, well read and well educated.”

His school was a huge melting point of cultures and languages and part of his mission is to bring that world to audiences in the US, UK and elsewhere. Techno-authoritarianism is here. That’s the message of the film: that it has already happened in many countries around the world. And there’s a terrifying and all too believable roadmap for Trump that is clearly laid out in 2073.

“Trump has been explicit about getting revenge on people. And now you have some of the richest and most powerful people in the world who became so through the collection of data. They’re now in power with someone who said, ‘I’m going to be a dictator’. It’s like Covid. When it happened in certain parts of the world, people kept thinking, we’re immune to it. It’s never going to happen. And it came and it rolled its way around the whole globe.”

It doesn’t always turn out that well for his subjects, says Kapadia. He’s thinking of Ayrton Senna, killed in a horror crash, Amy Winehouse, destroyed by drugs and alcohol, Ghost, who’s detained and interrogated. But what he’s suggesting in 2073, is that it’s almost too late – but not quite – for the rest of us too.

-

2073 opens in UK and Irish cinemas from 1 January